Between Arrival and Depature

by Dalia Jacobs, edited by Leena Aboutaleb

When I first arrived in Tunis, I was only supposed to stay for two weeks. It was a layover; temporary, unplanned, and unknown. I never study a place before I arrive. I prefer to land with my eyes open; to see a city through its people rather than curated lists and hyper-edited content.

Life, however, had other plans.

I was held at the airport for over five hours. I was questioned; not only because of the camera slung around my neck, but because of my background, both as a Palestinian and a humanitarian worker. They wanted a piece of paper from a higher entity, an institution, to prove my identity. For hours, I didn't feel real. Suspicion clung to me before I’d even fully stepped into the country. When they spoke, I couldn’t understand their dialect, aggravating the situation even more. Tunis greeted me with static. But even in that dissonance, I stayed.

I tried to leave. I couldn’t.

A slipped disc in my spine anchored me into place. Then, the geopolitical situation intensified, and so my bank account was frozen, reduced into my nationality. Movement became impossible. I had no choice but to stay even longer than I intended. Yet in that gravity, in that strange suspension, I was surrounded by light. I found myself surrounded by incredible souls; people who appeared just when I needed them, and who shared their time, spaces, and laughter without hesitation. Two Tunisian sisters and their mother became my chosen family.

Things weren’t always easy between us. There were ups and downs, as happens when strangers become close too quickly; when grief and exhaustion blur the lines of communication. The bond held. We kept showing up. They were there when I needed them, offering care and presence. Their care made the world feel a little less heavy. They felt familiar; the strength and tenderness I saw in Feriel and Farah felt as if I was looking into myself, seeing parts of myself in them. Feriel, especially, looks like my biological sister—something others often pointed out.

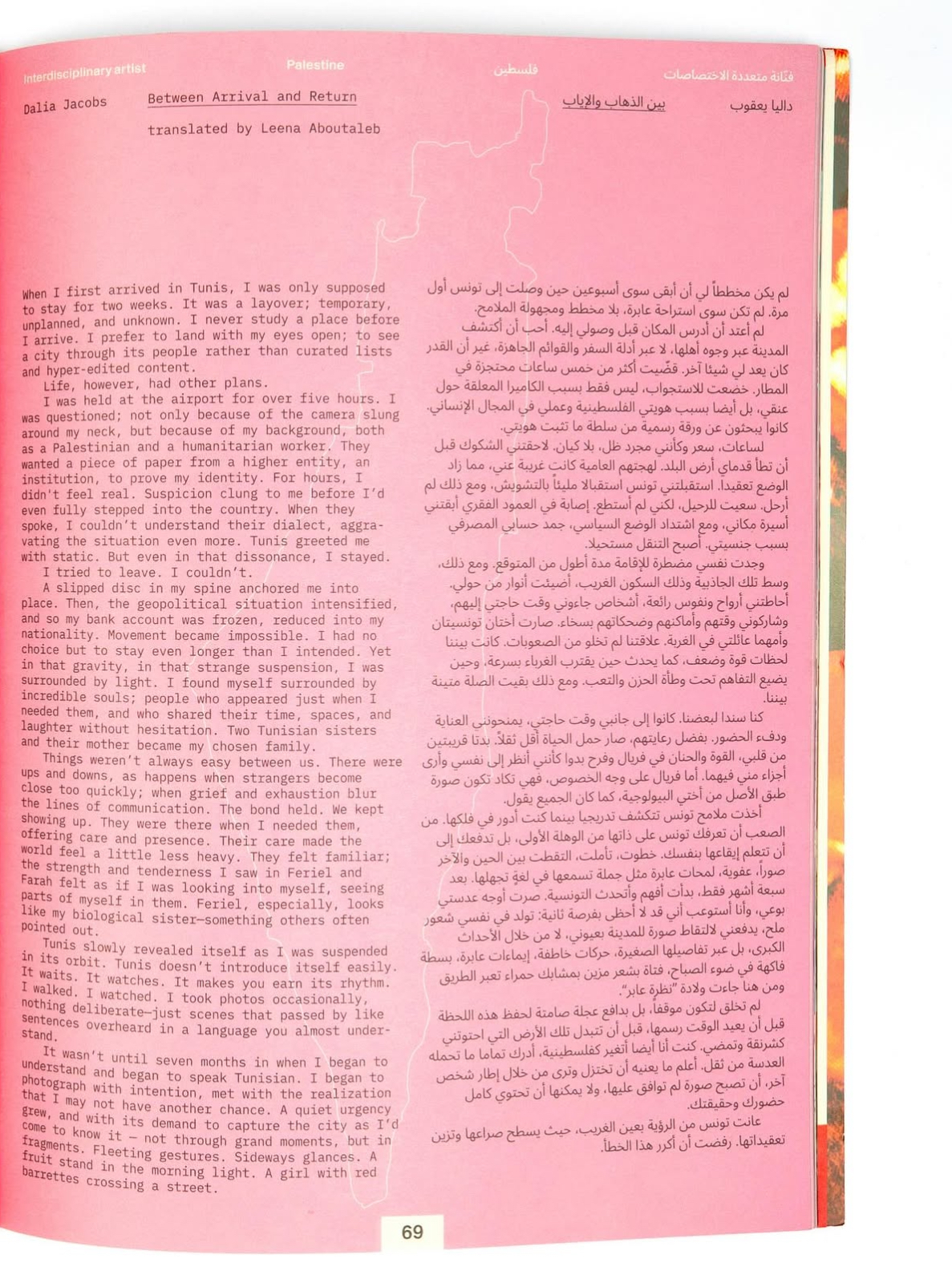

Tunis slowly revealed itself as I was suspended in its orbit. Tunis doesn’t introduce itself easily. It waits. It watches. It makes you earn its rhythm. I walked. I watched. I took photos occasionally, nothing deliberate—just scenes that passed by like sentences overheard in a language you almost understand.

It wasn’t until seven months in when I began to understand and began to speak Tunisian. I began to photograph with intention, met with the realization that I may not have another chance. A quiet urgency grew, and with its demand to capture the city as I’d come to know it — not through grand moments, but in fragments. Fleeting gestures. Sideways glances. A fruit stand in the morning light. A girl with red barrettes crossing a street.

That’s how Passenger’s View was born. Not as a statement, but in an urgency to capture this moment before the passage of time could reshape it, before the country that held me so gently, like a cocoon, transformed and moved on. I was changing too.

As a Palestinian, I’m acutely aware of the weight of the lens. I know what it means to be reduced and viewed through someone’s framing; made into an image you did not consent to, that does and cannot hold the fullness of our presence and truth. Tunisia has its own history of being looked at from the outside; its struggle simplified and its complexity aestheticized. I didn’t want to fall into such a trap. I didn’t seek out spectacle. I photographed as I passed humbly, quietly. The way you’d take notes in the margins of a book you didn’t write.

Still, I carried questions. What does it mean to photograph someone else’s world? What right do I have to frame a life I don’t entirely understand? Sometimes, I lowered the camera. Sometimes, I shot anyway, fearing the moment may never return.

In doing so, I realized Tunis had become a mirror. Its streets carried echoes of my homeland. The aftermath of colonization. The lingering tension of surveillance. The fierce softness of a people trying to live despite it all. More than anything, there was warmth.

Creating art in Tunis isn't easy. Space and resources are scarce. The struggle to make something honest that reflects your truth can feel endless. Yet people refuse to stay quiet, and they continue to create. It's a refusal to be silenced or forgotten; it's survival.

The people of Tunis are disarmingly kind and generous in ways that felt like home. The art scene pulses with young and talented sound engineers, photographers, and painters, all hungry to create and live fully. I found myself surrounded by dancers, filmmakers and artists whose creativity moves like a quiet revolution through the city. We shared conversations, dinners, doubts, and dreams. These friendships grounded me at a time, where I was free-falling, frozen in suspension by a world so much larger than myself.

One unforgettable moment was my first time in the South, meeting Alseed, who welcomed me into his family’s home without hesitation. There, I tasted the best Tunisian food and spent a week exploring villages and cities. I watched the sunrise over Chenini near Gabes and we kept coming back to one thought: time moves slower in the South. In its stillness, I felt what we say in Arabic— في بركة في الوقت —there is blessing in time. Barakeh was in the South.

Its stillness reminded me of my childhood, of my grandparent’s home; mornings stretched long and soft, where nothing felt immediate. The pace of the South held the same kind of ease, and in it, a feeling I hadn’t realized I missed.

I’ve come to believe that honest documentation isn’t about telling someone else’s story. It’s about standing beside them as it unfolds. Watching, witnessing, and understanding some things you can’t keep.

Tunis looked back at me gently, clearly. Somewhere between the chaos of arrival and the heartbreak of not being able to leave, I found something like home. Sometimes, you don’t choose a place. Sometimes, you are chosen and asked to stay, not forever, but just long enough to be changed in between its landscapes, its people.

Originally published by Sens · الإحساس Magazine, issue 1.

Life, however, had other plans.

I was held at the airport for over five hours. I was questioned; not only because of the camera slung around my neck, but because of my background, both as a Palestinian and a humanitarian worker. They wanted a piece of paper from a higher entity, an institution, to prove my identity. For hours, I didn't feel real. Suspicion clung to me before I’d even fully stepped into the country. When they spoke, I couldn’t understand their dialect, aggravating the situation even more. Tunis greeted me with static. But even in that dissonance, I stayed.

I tried to leave. I couldn’t.

A slipped disc in my spine anchored me into place. Then, the geopolitical situation intensified, and so my bank account was frozen, reduced into my nationality. Movement became impossible. I had no choice but to stay even longer than I intended. Yet in that gravity, in that strange suspension, I was surrounded by light. I found myself surrounded by incredible souls; people who appeared just when I needed them, and who shared their time, spaces, and laughter without hesitation. Two Tunisian sisters and their mother became my chosen family.

Things weren’t always easy between us. There were ups and downs, as happens when strangers become close too quickly; when grief and exhaustion blur the lines of communication. The bond held. We kept showing up. They were there when I needed them, offering care and presence. Their care made the world feel a little less heavy. They felt familiar; the strength and tenderness I saw in Feriel and Farah felt as if I was looking into myself, seeing parts of myself in them. Feriel, especially, looks like my biological sister—something others often pointed out.

Tunis slowly revealed itself as I was suspended in its orbit. Tunis doesn’t introduce itself easily. It waits. It watches. It makes you earn its rhythm. I walked. I watched. I took photos occasionally, nothing deliberate—just scenes that passed by like sentences overheard in a language you almost understand.

It wasn’t until seven months in when I began to understand and began to speak Tunisian. I began to photograph with intention, met with the realization that I may not have another chance. A quiet urgency grew, and with its demand to capture the city as I’d come to know it — not through grand moments, but in fragments. Fleeting gestures. Sideways glances. A fruit stand in the morning light. A girl with red barrettes crossing a street.

That’s how Passenger’s View was born. Not as a statement, but in an urgency to capture this moment before the passage of time could reshape it, before the country that held me so gently, like a cocoon, transformed and moved on. I was changing too.

As a Palestinian, I’m acutely aware of the weight of the lens. I know what it means to be reduced and viewed through someone’s framing; made into an image you did not consent to, that does and cannot hold the fullness of our presence and truth. Tunisia has its own history of being looked at from the outside; its struggle simplified and its complexity aestheticized. I didn’t want to fall into such a trap. I didn’t seek out spectacle. I photographed as I passed humbly, quietly. The way you’d take notes in the margins of a book you didn’t write.

Still, I carried questions. What does it mean to photograph someone else’s world? What right do I have to frame a life I don’t entirely understand? Sometimes, I lowered the camera. Sometimes, I shot anyway, fearing the moment may never return.

In doing so, I realized Tunis had become a mirror. Its streets carried echoes of my homeland. The aftermath of colonization. The lingering tension of surveillance. The fierce softness of a people trying to live despite it all. More than anything, there was warmth.

Creating art in Tunis isn't easy. Space and resources are scarce. The struggle to make something honest that reflects your truth can feel endless. Yet people refuse to stay quiet, and they continue to create. It's a refusal to be silenced or forgotten; it's survival.

The people of Tunis are disarmingly kind and generous in ways that felt like home. The art scene pulses with young and talented sound engineers, photographers, and painters, all hungry to create and live fully. I found myself surrounded by dancers, filmmakers and artists whose creativity moves like a quiet revolution through the city. We shared conversations, dinners, doubts, and dreams. These friendships grounded me at a time, where I was free-falling, frozen in suspension by a world so much larger than myself.

One unforgettable moment was my first time in the South, meeting Alseed, who welcomed me into his family’s home without hesitation. There, I tasted the best Tunisian food and spent a week exploring villages and cities. I watched the sunrise over Chenini near Gabes and we kept coming back to one thought: time moves slower in the South. In its stillness, I felt what we say in Arabic— في بركة في الوقت —there is blessing in time. Barakeh was in the South.

Its stillness reminded me of my childhood, of my grandparent’s home; mornings stretched long and soft, where nothing felt immediate. The pace of the South held the same kind of ease, and in it, a feeling I hadn’t realized I missed.

I’ve come to believe that honest documentation isn’t about telling someone else’s story. It’s about standing beside them as it unfolds. Watching, witnessing, and understanding some things you can’t keep.

Tunis looked back at me gently, clearly. Somewhere between the chaos of arrival and the heartbreak of not being able to leave, I found something like home. Sometimes, you don’t choose a place. Sometimes, you are chosen and asked to stay, not forever, but just long enough to be changed in between its landscapes, its people.

Originally published by Sens · الإحساس Magazine, issue 1.